The French Revolution was one of the most dramatic periods in history, defined by groundbreaking political change, social upheaval, and, yes, art. You might not think of paintings, prints, and sculptures as key players in revolutionary movements, but during this turbulent time, art wasn’t just decoration. It was a powerful tool used to shape ideas, influence people, and amplify both support for and resistance to the revolution. From arresting visual propaganda to stirring portrayals of revolutionary ideals, art during the French Revolution acted almost like a megaphone for those trying to sway public opinion. To understand its impact, we need to explore how art became a voice for both propaganda and protest during these years of dramatic change.

The French Revolution in a Nutshell

Before we dig into the art, it’s helpful to know what was happening in France during the revolution. The French Revolution began in 1789 and lasted a decade, ending in 1799. At its core, it was fueled by inequalities between the social classes and a growing frustration with the monarchy and its extravagance. Most of the population (the commoners) were struggling to survive, while the royals and nobles lived in luxury. This inequality sparked protests, which soon turned into full-blown rebellion.

The revolution wasn’t just about tearing down a monarchy. It was about reshaping society through liberty, equality, and fraternity. These grand ideas needed support from all parts of society, and this is where art came in. Paintings, prints, and sculptures became tools to spread revolutionary messages and rally the people.

Propaganda as a Revolutionary Weapon

Propaganda, in simple terms, is art or media created to influence people’s opinions or actions. During the French Revolution, propaganda played a central role in rallying support for revolutionary causes. Leaders needed the public on their side, and art helped stir emotions and unify people under a common vision.

Visualizing Revolutionary Ideals

One of the key ways propaganda worked was by symbolizing revolutionary ideas. For example:

- Liberty was often depicted as a strong, heroic woman. Artists would paint or sculpt her holding a torch or wearing a red Phrygian cap, a symbol of freedom during the revolution. This figure became a constant reminder of what the revolution was fighting for.

- Equality was frequently represented by images of peasants standing tall beside aristocrats or by scales balanced evenly. These visuals underscored the promise that all people, regardless of class, would have an equal voice.

Political Posters and Prints

Mass communication wasn’t what it is today, but the revolutionaries used posters, prints, and pamphlets to spread their messages. These materials often mocked the monarchy or depicted the triumph of “the people” rising against oppression. One famous image showed King Louis XVI being led to the guillotine, a stark and emotional depiction of justice as seen through revolutionary eyes.

These types of art were easy to produce and circulate, making them a vital tool for motivating both the literate and illiterate populations. People didn’t need to read lengthy texts; the images spoke for themselves.

Jacques-Louis David and Art’s Revolutionary Star

Jacques-Louis David was one of the most famous artists of the French Revolution, and his work embodied the power of propaganda better than almost anyone else’s. He wasn’t just any painter; he was a revolutionary himself, using his talent to support the cause.

One of David’s most iconic works is “The Death of Marat” (1793). This painting pays tribute to Jean-Paul Marat, a revolutionary who was assassinated in his bathtub by a political opponent. The image presents Marat as a martyr, with a calm and dignified expression despite his violent death. The painting turned Marat into a symbol of revolutionary sacrifice, inspiring others to rise up in his place.

David also organized public festivals that combined his artistic vision with political purpose. These events featured banners, statues, and elaborate designs aimed at uniting people and reminding them of their collective goals.

Protest Art and Dissent

While much of the art during the French Revolution supported the revolutionary cause, not everyone agreed with the events unfolding. Some artists used their work to critique the revolution, its leaders, or even its violent methods. Protest art became a way for these voices to challenge the status quo, often in subtle or coded ways.

Satirical Caricatures

Satirical art was a popular form of protest. Caricatures, which exaggerated features to ridicule a subject, were used to mock figures on all sides of the revolution. Often printed and distributed secretly, these pieces criticized revolutionary excesses or called out leaders for hypocrisy.

For example, some artists targeted men like Maximilien Robespierre, a leading figure during the revolution’s most radical phase, known as the Reign of Terror. These works poked holes in the perceived morality or authority of revolutionary leaders, helping to foster dissent among those who felt disillusioned.

Elegies for a Lost Order

Not everyone was happy to see the monarchy fall. Loyalists to the crown created art that mourned the old ways or highlighted the negative consequences of the revolution. Some of these pieces depicted tragic scenes of royal executions, showing King Louis XVI or Queen Marie Antoinette as sympathetic figures who suffered unjustly.

This type of protest art wasn’t widely accepted in revolutionary France, but it added an important layer to the artistic landscape, showing that there were still conflicting views during this time.

Art’s Role Beyond Politics

While much of the art from the French Revolution was political, it would be a mistake to overlook its broader significance. Artists pushed boundaries in both technique and subject matter, and their works remain powerful visual records of one of history’s most dramatic eras.

Innovation in Style

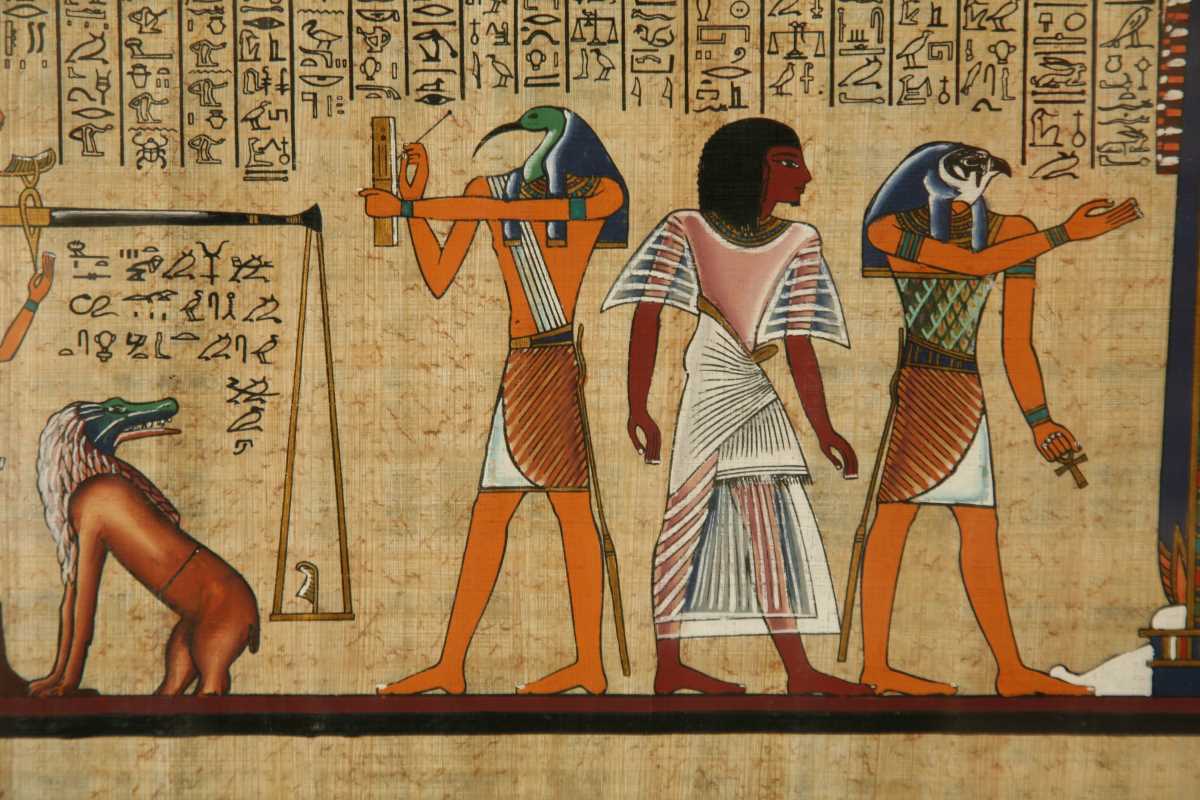

The French Revolution helped spur changes in artistic style. The opulent and decorative fashion of the royal court, known as Rococo, gave way to a simpler, more classical approach. This shift wasn’t just aesthetic; it reflected the desire for a return to the values of antiquity, like virtue and civic duty, ideals the revolutionaries aspired to.

This style, called Neoclassicism, emphasized clean lines, dramatic contrasts, and serious subject matter. It gave revolutionary art a sense of gravitas that matched the movement’s lofty ideals.

Preserving History

Art also served as a historical document. While much of what we know about the revolution comes from written records, paintings, sculptures, and prints give us a vivid glimpse into the emotions, events, and struggles of the time. They provide a visual narrative that words alone can’t capture.

(Image via

(Image via