Museums hold treasures from around the world, offering glimpses into cultures, histories, and traditions. But behind the glass displays and neatly written labels, there’s often a deeper story. Many of the items in museums were taken during the colonial period, a time when powerful nations controlled large parts of the world through conquest. Today, this has sparked a heated debate about whether these artifacts should stay in museums or be returned to their countries of origin.

At the center of this debate are questions about history, ownership, and justice. How did these items get to where they are? Who should they belong to now? And what role do museums play in preserving history versus perpetuating past injustices? To understand the complexities of this issue, we need to examine the history of colonialism, how artifacts came to be "collected," and why returning them remains a topic of global conversation.

The Colonial Era and the Collecting of Artifacts

The modern museum as we know it began to emerge during the colonial era, roughly between the 18th and early 20th centuries. At the time, European powers like Britain, France, and Belgium were expanding their empires across Asia, Africa, the Americas, and the Pacific. With expansion came the extraction of resources—not just gold, spices, or minerals, but also cultural treasures.

How Artifacts Were Taken

Artifacts often made their way to Europe through questionable means. Military conquests were a major source. When European forces defeated local rulers or communities, they would often seize sacred objects, jewelry, statues, or other items of value as spoils of war. One infamous example is the looting of the Benin Bronzes during a British raid on the Kingdom of Benin (in present-day Nigeria) in 1897. These stunning metal sculptures were taken forcefully and sold to museums and collectors.

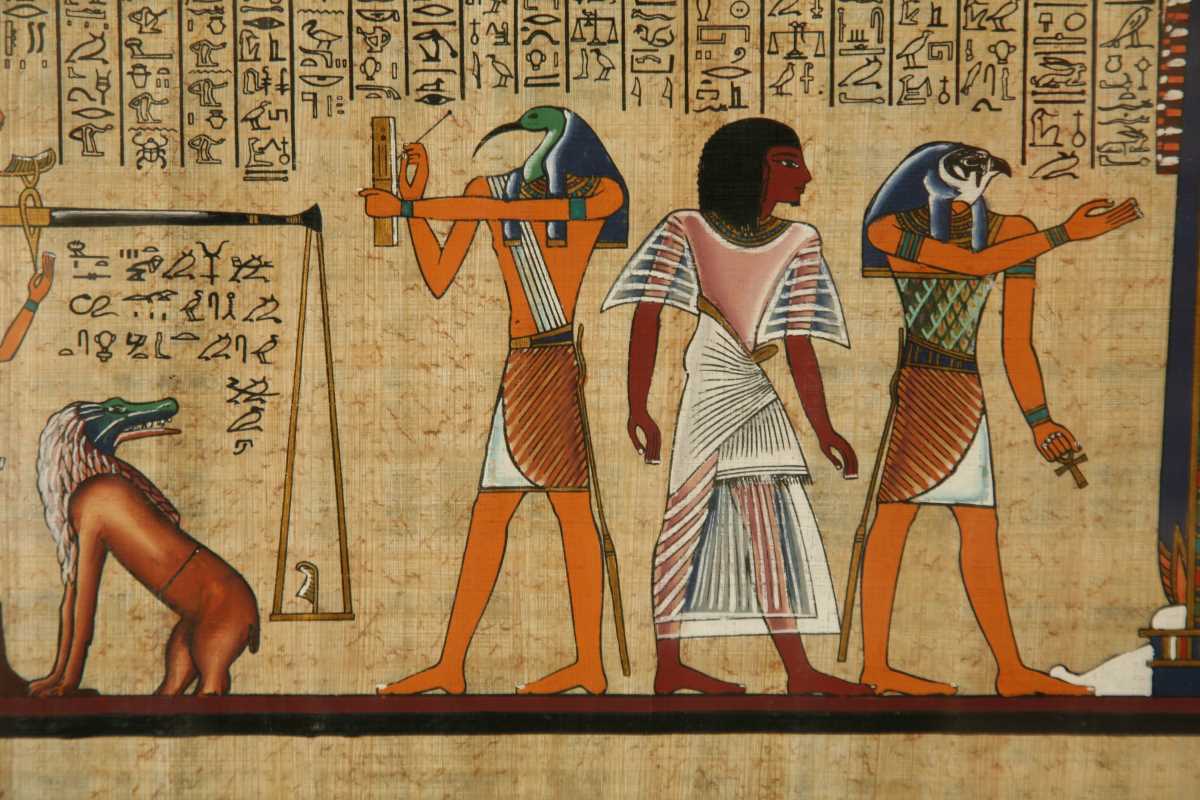

Other artifacts were taken under the pretense of "scientific discovery" or "preservation." Archaeologists and explorers funded by colonial governments often removed items from ancient sites without permission. The Rosetta Stone, a key artifact for deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs, was taken by the British from French-controlled Egypt in 1801, during the Napoleonic Wars.

Some objects were acquired through trade or gifts. However, these exchanges were often unequal. Indigenous communities might have traded valuable cultural items without fully understanding their importance to European collectors or under the pressure of colonial power dynamics.

Why This History Matters

For many of the countries and cultures from which these items were taken, these artifacts hold deep spiritual, cultural, or historical significance. They connect people to their heritage and tell stories of their ancestors. When such objects are removed, it’s not just about losing physical items. It also disrupts traditions, cultural identity, and the ability to pass down knowledge through generations.

At the same time, some defenders of museums argue that these institutions have preserved many artifacts that might have been lost, damaged, or destroyed if left in their original locations, particularly in areas affected by wars or instability. This raises a complicated question about preservation and whether the ends justify the means.

The Push for Repatriation

Repatriation is the process of returning cultural property to its country or community of origin. Over the last few decades, there has been growing pressure on museums to repatriate stolen or looted artifacts. Countries like Greece, Egypt, Nigeria, and others have asked major institutions to return items taken during colonial times.

Notable Repatriation Cases

The Parthenon Marbles

Also known as the "Elgin Marbles," these sculptures were taken from the Parthenon in Athens by Lord Elgin in the early 1800s. They’ve been housed in the British Museum for over 200 years. Greece has repeatedly requested their return, arguing that they’re part of its cultural heritage and should be reunited with the rest of the Parthenon. The British Museum, however, maintains that it legally acquired the marbles and has preserved them for global audiences.

The Benin Bronzes

Thousands of Benin Bronzes were looted by British forces in 1897 and distributed to museums worldwide, including the British Museum and institutions in the U.S. and Germany. Nigeria has been vocal about wanting these works returned, and recently, several European museums have agreed to begin repatriating items from their collections.

Indigenous Australian Regalia

Many sacred artifacts from Indigenous Australian communities, including ceremonial objects and ancestral remains, were taken during colonization. Efforts to return these items are ongoing, often involving agreements between tribal elders and museums in places like the U.S. and Europe.

Arguments For and Against Repatriation

The debate over stolen artifacts is far from simple. Both sides have strong arguments that reveal the complexities of cultural heritage and historical accountability.

Arguments for Repatriation

Restoring Cultural Heritage

- Artifacts are part of a community’s identity. Returning them allows cultures to reclaim their stories and pass them on to future generations.

Moral Responsibility

Many items were taken without consent or under conditions of coercion. Returning them is a way to address historical injustices and acknowledge the harm caused by colonialism.

Decolonizing Museums

Critics argue that museums built during the colonial era continue to center European narratives at the expense of other cultures. Repatriation is seen as a step toward creating a more inclusive and equitable understanding of history.

Arguments Against Repatriation

Preservation and Access

Some argue that museums provide a safe environment for preserving fragile artifacts, especially in regions facing political instability or lack of resources to manage large collections.

Shared Global Heritage

Museums often frame their collections as part of a shared human history, accessible to people from all over the world. Removing key artifacts could limit public access to these cultural treasures.

Legal Objections

Institutions like the British Museum often argue that artifacts were acquired legally according to the standards of the time and that current laws don’t require their return.

(Image via

(Image via